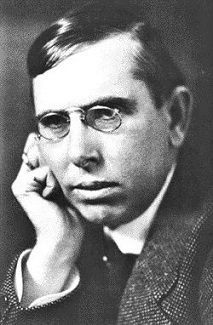

On page 335 of Craig Brandon’s Murder in the Adirondacks: An American Tragedy Revisited (Fully Revised and Expanded Edition, 2016) — considered to be the definitive book about the “American Tragedy” murder case — Brandon states:

In the novel [Theodore Dreiser’s An American Tragedy], Sondra is with Clyde when he is arrested, and she comes to visit him when he is in prison, something that is very unlikely to have happened in real life.

Actually, this is not the case with respect to the novel. Brandon is conflating the novel with the 1951 movie version, A Place in the Sun. It is questionable whether he has actually read An American Tragedy.

In Dreiser’s An American Tragedy, Clyde Griffiths receives a letter from Sondra Finchley when he is on death row (Book Three, Chapter XXXII; see below). The letter is typewritten with no signature.

Sondra does not visit Clyde in prison at any point in the novel.

Clyde is despondent after receiving the letter because of its terseness, formality, and impersonal character.

The overrated film A Place in the Sun has been the source of much confusion in this regard. In the film, which takes shameless liberties with Dreiser’s novel, Angela Vickers (Sondra Finchley), played by Elizabeth Taylor, visits George Eastman (Clyde Griffiths), played by Montgomery Clift, on death row.

The film ends with Angela visiting George in prison, saying that she will always love him, and with him slowly marching towards his execution.

This is – to put it kindly – ridiculous. It undercuts and violates the plot of the novel and premises about the central characters upon which it was based.

— Roger W. Smith

June 2016

**************************************************

[T]he film is a travesty of Dreiser’s novel. … An example of the compromise involved—typical in Hollywood films, which is why so few can be taken seriously as social comment—occurs in the final scene when George [the Clyde Griffiths character] is in jail awaiting execution. Sondra visits George in his cell and expresses her love for him. The book makes it explicitly clear that once her lover was in trouble and had become a social undesirable, this rich girl wanted nothing more to do with him. The scene in the film is the antithesis of realism.

— Charles Higham on A Place in the Sun, in The Art of the American Film 1900-1971 (1973)

**************************************************

Addendum:

Theodore Dreiser, An American Tragedy, Book Three, Chapter XXXII:

But the days going by until finally one day six weeks after–and when because of his silence in regard to himself, the Rev. Duncan was beginning to despair of ever affecting him in any way toward his proper contrition and salvation–a letter or note from Sondra. It came through the warden’s office and by the hand of the Rev. Preston Guilford, the Protestant chaplain of the prison, but was not signed. It was, however, on good paper, and because the rule of the prison so requiring had been opened and read. Nevertheless, on account of the nature of the contents which seemed to both the warden and the Rev. Guilford to be more charitable and punitive than otherwise, and because plainly, if not verifiably, it was from that Miss X of repute or notoriety in connection with his trial, it was decided, after due deliberation, that Clyde should be permitted to read it–even that it was best that he should. Perhaps it would prove of value as a lesson. The way of the transgressor. And so it was handed to him at the close of a late fall day–after a long and dreary summer had passed (soon a year since he had entered here). And he taking it. And although it was typewritten with no date nor place on the envelope, which was postmarked New York–yet sensing somehow that it might be from her. And growing decidedly nervous–so much so that his hand trembled slightly. And then reading–over and over and over–during many days thereafter: “Clyde ? This is so that you will not think that some one once dear to you has utterly forgotten you. She has suffered much, too. And though she can never understand how you could have done as you did, still, even now, although she is never to see you again, she is not without sorrow and sympathy and wishes you freedom and happiness.”

But no signature–no trace of her own handwriting. She was afraid to sign her name and she was too remote from him in her mood now to let him know where she was. New York! But it might have been sent there from anywhere to mail. And she would not let him know–would never let him know–even though he died here later, as well he might. His last hope–the last trace of his dream vanished. Forever! It was at that moment, as when night at last falls upon the faintest remaining gleam of dusk in the west. A dim, weakening tinge of pink–and then the dark.

He seated himself on his cot. The wretched stripes of his uniform and his gray felt shoes took his eye. A felon. These stripes. These shoes.